A salute to Black Hollywood trailblazers who put their unforgettable mark on the entertainment industry and forever altered the way society looked at race.

By Scott Huver

Actor and filmmaker Sidney Poitier recognized the power of representation well before the height of his career in the 1960s as the most acclaimed and popular Black screen leading man in Hollywood. “I knew what it was to be uncomfortable in a movie theater watching unfolding on the screen images of myself – not me, but Black people – that were uncomfortable,” he once said. And he realized that through his own stereotype-defying portrayals he could have a seismic impact on the culture –as he later put it, “I did not go into the film business to be symbolized as someone else’s vision of me.”

“My talent was the weapon, the power, the way for me to fight,” entertainer Sammy Davis, Jr., once said of what he had to rely on when facing what must have seemed like near impossible odds for a Black performer to succeed in show business on a level anywhere close to his white contemporaries. “It was the one way I might hope to affect a man’s thinking.” And yet, defying the pernicious systemic racism that pervaded American society then in his, even in more enlightened, progressive Hollywood – and even more overt and potentially life-threatening than today – succeed Davis did.

Poitier and Davis’ faith in their peerless abilities to entertain fueled their rise to the upper echelons of superstardom, but not without risk, struggle, criticism or heartbreak. They achieved their dreams, and along the way they ranked among an important collection of trailblazing figures in Hollywood in film, music and television who forged paths for other artists of color to follow, and also over time reshaped and recast the way white audiences in particular perceived not just Black entertainers but Black people and the respect and equality they deserved.

Let The Voluntourist acquaint you with 16 of Hollywood’s brightest early beacons from its early Golden Age through the end of the turbulent 1960s, who along with charming and riveting audiences with their undeniable array of talents, the also broke down racial barriers both on screen and off, whether it be in how they played a role, the kinds of audiences they performed for, where they lived or who they shared their lives with. They also, by and large, used their groundbreaking successes, high visibility and generous philanthropy to uplift others and clear the path for succeeding generations, championing causes with repercussions that would reverberate far beyond the soundstages of Hollywood, the stages of Broadway and the showrooms of Las Vegas.

Josephine Baker

Having already conquered vaudeville, Broadway and the elite Parisian revue circuit with her stunning sex appeal, charming comedic timing, powerful singing voice and brilliantly executed, taboo-testing choreography during the freewheeling Jazz Age, the American-born-baker Baker and her scandalous banana dance launched an international sensation, and she became the first Black women to headline major motion pictures during her silent film career in France.

Along with all her professional accomplishments, she put the clout that came with her fame to potent use: during the Nazi occupation of France during World War II, she used her access to café society figures and officials to secretly gather valuable intelligence to aid the French Resistance, and carried secret information to the Allied Forces while traveling on tour through Europe.

In the 1950s she toured her native America, steadfastly refusing to allow the venues in which she performed to segregate their audiences and publicly exposing the hotels that refused to allow her to stay. Her stand specifically helped begin integration in New York nightclubs and Las Vegas resorts, until a Communist smear campaign waged by powerful journalist Walter Winchell derailed her engagements. Along with living a vibrant life that included multiracial and bisexual relationships, she was an ardent supporter of the NAACP, and the only female speaker at Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s March on Washington in 1963.

Key works: “Siren of the Tropics (1927),” “Princess Tam Tam” (1935).

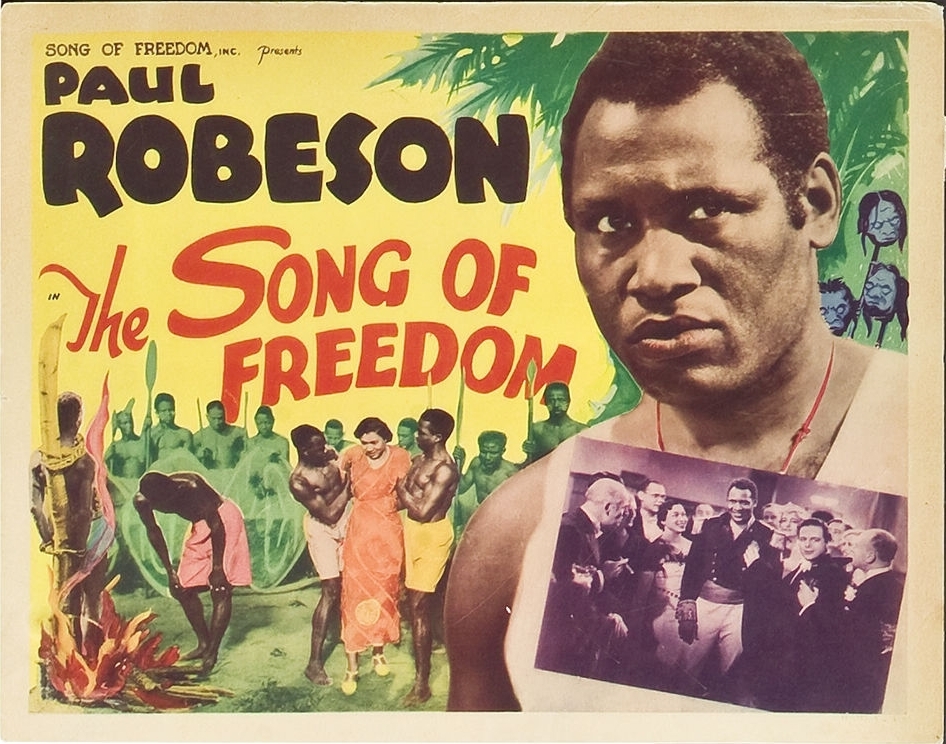

Paul Robeson

As only the third Black student ever admitted to Rutgers University, a Phi Beta Kappa, an All-American collegiate football player and a Columbia Law School graduate, all in the restrictive 1910s and ‘20s, Robeson was an accomplished trailblazer before his performing career even began. But it was his presence on the stages of the Harlem Renaissance – as an arrestingly powerful dramatic actor, a mesmerizing orator and a transcendent baritone singer – that made him a star, leading to celebrated theatrical productions around the world and a European film career that led him to become one of top box office stars in the United Kingdom during the 1930s.

Photo courtesy of American Pop Classics

Photo courtesy of American Pop Classics

Returning to the United States at the outbreak of World War II, Robeson quickly became a multimedia phenomenon, working in film, stage, recordings and radio. He was the first Black actor to play Shakespeare’s Othello on Broadway, but he ultimately rejected a Hollywood career due to the frequently demeaning nature of the roles he was offered. Instead, his political activism rose to the forefront: among many causes, he exposed the hotels who refused his business, lobbied for Major League Baseball to admit Black athletes, founded the American Crusade Against Lynching and – due to the non-racist treatment he’d received during his visits to Moscow – became a vocal proponent of socialism.

His staunch refusal to soft-peddle his beliefs and disavow his continued advocacy of Marxism would ultimately lead Robeson to run afoul of the notorious red-hunting House Unamerican Activities Committee in the 1950s, resulting in his widespread blacklisting, the revocation of his passport and an active campaign to discredit him. Though silenced in America, Robeson would ultimately travel the world fighting tirelessly for the causes he championed. As McCarthyism eventually subsided, his activist legacy would receive renewed acclaim.

Key works, film: “Show Boat (1936),” “Song of Freedom” (1936), “The Proud Valley” (1940).

Hattie McDaniel

The daughter of former slaves, McDaniel’s path in show business proved consistently bittersweet. An accomplished singer and songwriter before becoming a Hollywood actress, she nevertheless had to work as a domestic between jobs to make ends meet. Even after breaking through on screen in films by perfecting amusingly opinionated maid roles in the 1930s opposite stars like Mae West and Shirley Temple and befriending the Hollywood elite, she faced criticism from Black audiences for perpetuating racial stereotypes, while racist white audiences took offense at her deftly stealing scenes from white stars.

Vivien Leigh and Hattie McDaniel in Gone with the Wind

Vivien Leigh and Hattie McDaniel in Gone with the Wind

Photo courtesy of Warner Bros. and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Even her landmark role as Mammy in the 1939 classic “Gone With the Wind” came with double edges: the studio refused to let her attend the premiere in Atlanta for fear of riling Southern audiences – even her friend Clark Gable’s threat to boycott the event didn’t deter the decision (McDaniel talked him out of it). But on screen, McDaniel – who connected with the role because she recognized aspects of her grandmother in it – scored a triumph, and she was rewarded by being named the first Black performer to receive an Academy Award, for Best Supporting Actress. Even that was not a clear-cut victory, however: the hotel where the Oscar ceremony briefly lifted its whites-only policy to allow her to attend, but sat her at a segregated table and did not allow her to enter its nightclub for the afterparty.

Nevertheless, her thriving film career segued neatly into new mediums: she became the first Black actor to star in her own radio show, the popular comedy “Beulah,” and she became a staple in early television as well. And she was among a group of prosperous Black actresses in her Los Angeles neighborhood who successfully won the right to prevent the area from being segregated due to antiquated racist land covenants. Whatever the problematic elements of some of the roles she played, McDaniel broke down barriers of visibility on screen and off, and demonstrated that the highest pinnacles of artistic and financial success were not out of reach for Black Americans.

Key works, film: “The Little Colonel” (1935), “Alice Adams” (1935), “Show Boat” (1936), “Gone With the Wind (1939), “In This Our Life” (1942); radio: “Beulah” (1945-1954).

Eddie “Rochester” Anderson

A vaudeville performer since his early teens, Anderson made a name for himself as a dancer and comedian, known for his inimitable gravelly/squeaky voice. He enjoyed a burgeoning film career, and after a string of well-received guest appearances on radio’s hugely successful “The Jack Benny Program,” in 1937 Benny and his writers created the character of Rochester Van Jones, Benny’s wisecracking valet, specifically for Anderson, making him the first Black actor to have a regular role on a national radio broadcast.

Lena Horne and Eddie “Rochester” Anderson in Cabin in the Sky

Lena Horne and Eddie “Rochester” Anderson in Cabin in the Sky

Photo courtesy of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Despite the stereotypical role as a servant, he bucked convention by always getting the better of his vain and stingy boss, and the listeners embraced him for it – during the radio run and the subsequent television series, live audience enthusiasm for Anderson frequently eclipsed even applause for Benny. Throughout the 1940s he was the highest paid Black performer in show business, and one of the wealthiest men in America.

His incredible popularity made him an in-demand presence in films, including classics such as “You Can’t Take It With You,” “Gone With the Wind,” “Cabin In the Sky” and “Brewster’s Millions” (a film banned in the South for being too racially progressive). Meanwhile, Benny – long a champion of equality and increasingly close with Anderson – instructed his writers to downplay any ethnic stereotypes: Rochester’s comic quirks were to be his own, and no jokes were to be made at the expense of his race, though Benny’s whiteness was fair game. When the production visited other cities, the cast and crew stood in solidarity with Anderson whenever a hotel refused to accommodate him.

Away from the screen, Anderson was known as an especially astute businessman – he owned racehorses and manufactured parachutes for the military during World War II, among other ventures – and he was successfully voted the honorific title of mayor of Los Angeles’ Central Avenue, using his position to encourage Black aviators to serve the U.S. in the war. In L.A.’s West Adams, where he made his home, he led a Black revitalization of the neighborhood, defying racist land covenants designed to ban minorities.

His magnificent home designed by the prominent Black architect Paul Williams, became such a landmark, the street was renamed Rochester Avenue. Anderson’s comedic skill and lovable demeanor was crucial in showing audiences that rather than laughing at stereotyped roles, they could laugh with clever, witty Black characters that they welcomed into their homes each week like familiar friends.

Key works, radio and television: “The Jack Benny Program” (radio,1937-1955; television, 1950-1965); film: “Show Boat” (1936), “The Green Pastures” (1936), “You Can’t Take It With You” (1938), “Gone With the Wind” (1939), “Buck Benny Rides Again” (1940), “Cabin In the Sky” (1943), “Brewster’s Millions” (1945).

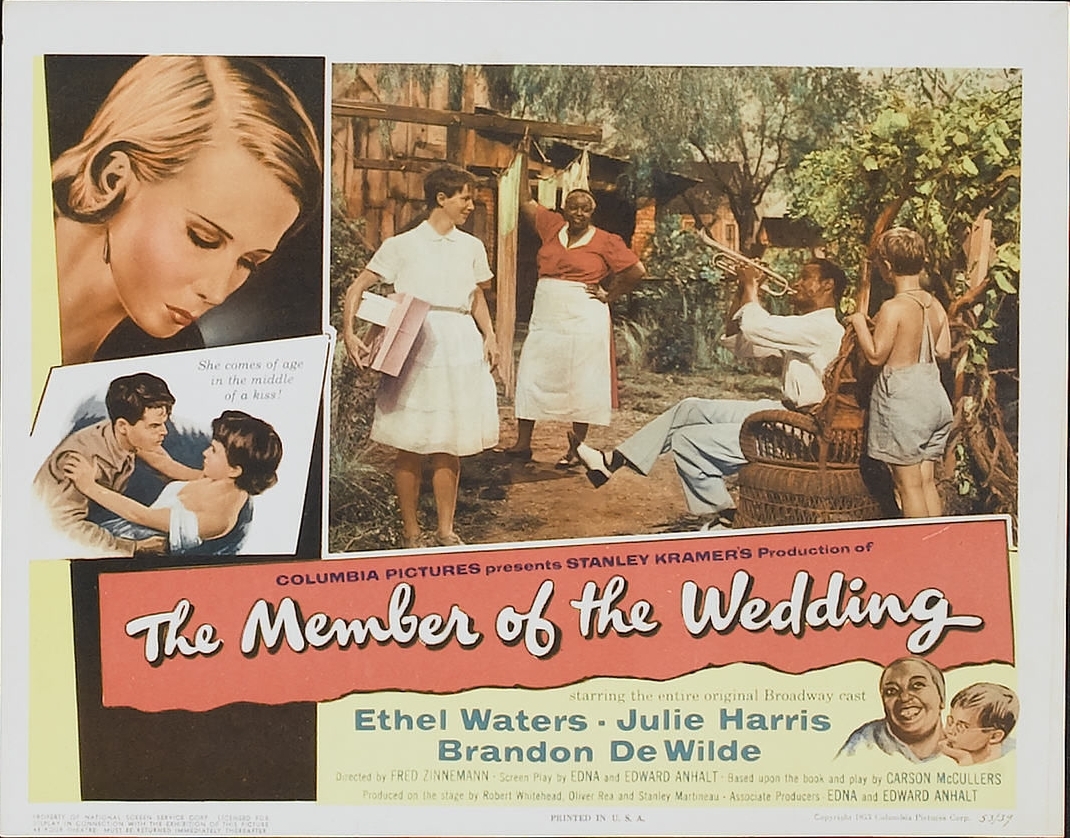

Ethel Waters

Like so many performers of her era, Waters built her career through stints on the Black vaudeville circuit and in nightspots like the Cotton Club, making her mark as a blues singer, After recording several hit songs during the 1920s, becoming the highest paid Black recording artist and stage performer of the day and the first to truly integrate the Broadway theater district. When Hollywood beckoned, she became a scene-stealer in films made specifically for Black audiences like “Cabin In the Sky,” as well as popular mainstream studio fare like “Member of the Wedding.”

Photo courtesy of Columbia Pictures

Photo courtesy of Columbia Pictures

In 1949 she became only the second Black actor nominated for an Academy Award, as Best Supporting Actress for “Pinky,” playing the grandmother of Jeanne Crain’s white-passing title character. On television, Waters continued to break boundaries: as early as 1939, she became the first Black performer to star in a TV variety special; in 1950 she shattered color barriers again when she became TV’s first black lead in a nationally broadcast weekly series, the adaptation of the hit radio comedy “Beulah” for the first season.

Waters would depart the series after growing concern that it perpetuated negative racial stereotypes, and would remain a fixture on stage, in film and on television, and – as a born-Again Christian following many personal travails – joined Rev. Billy Graham on his touring crusades late in her life.

Key works, music: “Dinah” (single, 1925), “Am I Blue” (1929), “Stormy Weather” (single, 1933); film: “Cairo” (1942), “Cabin In the Sky” (1943), “Pinky” (1949), “Member of the Wedding” (1942); television: “Beulah” (1950-1951).

Lena Horne

Brooklyn-born Horne began her career at Harlem’s legendary Cotton Club as a teenager in the 1930s, rising from the chorus line to become an in-demand vocalist in New York nightclubs and radio broadcasts before decamping to Hollywood to headline at the Little Troc on the Sunset Strip. Instantly embraced by movie star society, Horne – as photogenic as she was melodic – quickly nabbed a studio contract. Her filmic rendition of the title song for 1943’s all-Black musical “Stormy Weather” instantly became her signature song, and she would appear in other creative triumphs aimed at Black audiences like 1943’s “Cabin In the Sky,” as well as numerous mainstream MGM musicals – although she was denied leading roles when starring opposite white performers and her scenes were usually designed as standalones that could be edited out of film prints showing in the South.

Lena Horne and Bill Robinson in Stormy Weather

Lena Horne and Bill Robinson in Stormy Weather

Photo courtesy of Twentieth Century-Fox

After losing the coveted role of biracial Julie La Verne in 1951’s “Showboat” to her close, non-musical, white friend Ava Gardner, Horne gradually shifted away from the too-typecast film roles being sent her way and focused instead on her red-hot international nightclub career, which in turn fueled a wildly successful recording output, a ubiquitous presence on television and a stint on the Broadway stage, leading her to become the first Black woman to be nominated for a Tony Award for “Jamaica” in 1958 – she’d be awarded a special Tony (along with some Grammys) over two decades later for “Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music,” still the record-holder for the longest-running solo performance in Broadway history.

Along with providing a valuable point of representation on screen and stage, Horne also led the way on activism: refusing to perform for segregated audiences in her USO tours during World War II, she ultimately self-financed her own performances for U.S. troops. She was the first Black performer appointed to the board of the Screen Actors Guild, and actively involved in the civil rights movement – rallying with NAACP leader Medgar Evers, meeting with President John F. Kennedy, marching with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and weathering pressure over her interracial marriage to conductor Lennie Hayton. Horne’s long, vital career and personal accomplishments stand as a testament to sheer talent and will ultimately overcoming institutional obstacles.

Key works, film: “Cabin In the Sky” (1943), “Stormy Weather” (1943), “Till Clouds Roll By” (1946), “Words and Music” (1948), “The Wiz” (1978); music: “Stormy Weather “ (1957), “Lena Horne at the Waldorf Astoria” (1958), “Lena Horne at the Sands” (1961), “Porgy and Bess” (1962), “The Lady and Her Music: Live on Broadway” (1981).

Nat “King” Cole

Cole’s dizzying piano playing was the centerpiece of his jazz combo’s early performances, but when he added his distinctive, smoky-smooth vocals into the mix, a string of smash hit pop records – including enduring classics such as “Sweet Lorraine,” “”The Christmas Song,” “(Get Your Kicks on) Route 66,” “(I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons,” “Mona Lisa” and “Unforgettable” – followed through the 1940s and ‘50s.

Photo courtesy of Alex Gottlieb Productions

Photo courtesy of Alex Gottlieb Productions

Along the way, he broke color barriers in radio program sponsorship and, in 1956, his variety television series “The Nat ‘King’ Cole Show” debuted on NBC, the first TV show to be hosted by a Black performer. Despite the show’s superstar host and A-list musical guests, including Ella Fitzgerald, Tony Bennett, Mel Torme and Peggy Lee, it was unable to secure a national ad sponsor and ceased production after 42 episodes. Nevertheless, Cole’s recording and live performance careers would continue to flourish for years, until his death from cancer at age 45.

Throughout his career Cole would contend with particularly ugly acts of racism, even at the heights of his stardom: when he purchased a home in Los Angeles’ elite Hancock Park neighborhood in 1948, he not only faced opposition from several white neighbors, the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross on his front lawn – but he remained steadfast and became a longtime pillar of his community. In 1956, after a widespread conspiratorial smear campaign focused on Cole’s possible interracial romances, a group of white Klansmen assaulted him onstage during a concert in Birmingham, Alabama, attempting to kidnap him, but were thwarted by police – though Cole was injured in the melee.

The singer also faced criticism from the Black community when he performed for all-white audiences; as a result, Cole boycotted segregated venues and embraced visibly supporting the civil rights movement, helping plan the 1963 March on Washington and consulting on racial issues with Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson.

Key works, music: “The King Cole Trio, Vol. 1-IV” (1943-49), “Unforgettable” (1954), “After Midnight” (1957), “Just One of Those Things” (1957), “The Magic of Christmas” (1960), “Nat King Cole Live at the Sands” (1966); television: “The Nat King Cole Show “(1956-1957); film: “St. Louis Blues” (1958).

Sidney Poitier

From the onset of his career in film in the 1950s, handsome, charismatic and riveting Sidney Poitier daringly took on roles that made pointed statements on race, deepening the portrayal and agency of Black characters as well as his own on-screen profile with each new performance. In “No Way Out,” he played a young prison doctor caught in conflict with a bigoted criminal whose brother died under his care; he was a gifted but angry, antisocial student in “The Blackboard Jungle;” and a convict chained to his white fellow escapee Tony Curtis in “The Defiant Ones.” The combination of his explosive talent, exciting choices and box office success quickly cemented him as the most in-demand Black leading man Hollywood had ever seen, and the first to compete for the Academy Award.

As his fame and opportunities increased, Poitier continued to push conventional boundaries in his film work, including 1959’s “Porgy and Bess,” 1961’s “A Raisin in the Sun” (reprising his Tony-nominated Broadway role) and “Paris Blues” and 1963’s “Lilies of the Field,” for which he won the Best Actor Oscar and Golden Globe – the first Black man to do so in both cases.

Katharine Houghton and Sidney Poitier in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner

Katharine Houghton and Sidney Poitier in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner

Photo courtesy of Columbia Pictures

In 1967 he pulled off the remarkable feat of starring in three of the year’s most talked-about, socially relevant films – “To Sir With Love,” “In the Heat of the Night” (which spawned two Poitier-centric sequels) and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” – and becoming the most popular and bankable movie star, Black or white, of the moment. Later, he would establish himself as the director of a string of hit comedies of the 1970s; in the 1990s he joined the Board of Directors of The Walt Disney Company and served as the Bahamian Ambassador to Japan.

On screen Poitier’s artistry reshaped a generation’s views on race in America – even as he was privately concerned that he was playing too many idealized paragons and missing out on more complex, challenging roles. Off-screen he was a tireless crusader for civil rights, helping plan, fund and attend some of the movement’s most historic moments, including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s March on Washington in 1963. Among a staggering array of prestigious acknowledgements of his contributions – including the Kennedy Center Honors, an Honorary Academy Award, the American Film Institute’s Life Achievement Award and the NAACP Image Awards’ Hall of Fame – Poitier has also been knighted by Queen Elizabeth II and awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor, by President Barack Obama.

Key works, film, acting): “Porgy and Bess” (1959), “A Raisin in the Sun” (1961), “Paris Blues” (1961), “Lilies of the Field” (1963), “To Sir With Love” (1967), “In the Heat of the Night” (1967), “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” (1967), Uptown Saturday Night” (1974); film, directing: “Uptown Saturday Night” (1974), “Stir Crazy” (1980); television, acting: “Separate But Equal” (1991), “Mandela and de Klerk” (1997).

Dorothy Dandridge

A nightclub singing sensation prior to her Hollywood career, Dandridge’s star rose gradually throughout the 1940s in films for both Black-specific and general audiences in roles that focused on her musical and acting abilities and, increasingly, her stunning beauty. Indeed, to land her coveted breakthrough role in the 1954 film adaptation of the all-black Broadway musical “Carmen Jones,” Dandridge deftly made herself over into an earthy bombshell and, in the wake of her star-making performance, became Hollywood’s debut mainstream Black sex symbol, the first Black woman to grace the cover of LIFE Magazine, and the first African American, male or female, nominated for an Academy Award in a leading role.

Photo courtesy of RKO Radio Pictures

Photo courtesy of RKO Radio Pictures

With follow-up roles in films like “Island In the Sun” and “Porgy and Bess” (for which she was nominated for a Golden Globe) and an ever-exploding nightclub career, Dandridge stood at the brink of bona fide superstardom, even though, as when she was booked in Las Vegas, she was often denied the same services and accommodations as the white guests who took in her bravura live performances. But along with systemic racism, her career would too often be hamstrung by her injudicious romantic choices, financial troubles, guilt over feeling somehow the cause of her special needs daughter’s challenges and personal scandals both real and fabricated.

Still, throughout her career, Dandridge would continue to shatter color barriers – especially as the first-ever Black female performer in many clubs, paving the way for countless performers to follow – and was a staunch supporter of civil rights causes like the NAACP (despite being harassed by the FBI for her association with such groups). And she definitively established that a Black woman could be as viably sexy on screen – and a similarly mesmerizing actress – as her white peers like Marilyn Monroe. Tragically, also like Monroe, she died mysteriously in her prime at age 42, with no second act to demonstrate what she might have been capable of achieving.

Key works, film: “Carmen Jones” (1954), “Island In the Sun” (1957), “Porgy and Bess” (1959).

Harry Belafonte

The startlingly handsome, mellifluously voiced Jamaican-born performer began his career on parallel tracks: as a musician with an abiding love for the island rhythms of his home country as well as a cultivated passion for traditional folk music; and as an arresting actor – the first-ever Black male Tony winner, for “John Murray Anderson’s Almanac” in 1954 – whose marquee looks were ready-made for an evolving film audience. His movie stardom was minted when he appeared opposite frequent co-star Dorothy Dandridge in 1954’s all-Black musical “Carmen Jones,” followed two years later by his chart-topping album “Calypso,” which introduced American audiences to that musical genre and became the first LP to sell over one million copies within a year.

Continuing his career in its varied fashion, Belafonte continued to record top-selling and Grammy-winning albums in a variety of musical styles (soon-to-be-famous Bob Dylan played on one of his albums), headline concert and nightclub performances around the world, host Emmy-winning television specials and even perform at the 1960 inaugural for President John F. Kennedy, who named him cultural ambassador to the Peace Corps.

Dorothy Dandridge and Harry Belafonte in Carmen Jones photo courtesy of Twentieth Century Fox

Dorothy Dandridge and Harry Belafonte in Carmen Jones photo courtesy of Twentieth Century Fox

Meanwhile, his film career heyday would include racially controversial but compelling roles in “Island In the Sun,” the film noir classic “Odds Against Tomorrow” and the post-apocalyptic “The World, the Flesh and the Devil,” as well as later career turns like “Kansas City” and “BlaKkKlansman.” When the white British singer Petula Clark affectionately touched Belafonte’s arm while taping an NBC special, there was a pre-airing objection from an exec at advertiser Plymouth Motors, but the stars and network stood strong: the subsequent ratings were stellar, and the car company’s ad manager lost his job.

Off-screen, Belafonte has an unequaled role as a civil rights champion, social justice advocate, political activist and generous humanitarian. A close confidant of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., he endured blacklisting while financing a significant portion of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, including the 1961 Freedom Rides, raising bail for King and other leaders jailed in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963 and appearing alongside King at the March on Washington.

His decades-long support of human rights issues across the globe include appearing at Live Aid and helping organize the watershed all-star “We Are the World” recording session for famine relief in Africa, both in 1987. He continues to lend his voice and his name to a litany of causes, movements and political campaigns, and has been awarded with nearly every significant cultural award both inside and outside of the entertainment industry.

Key Works, film: “Carmen Jones” (1954), “Island In the Sun (1957), “Odds Against Tomorrow” (1959), “Uptown Saturday Night” (1972), “Kansas City” (1996), “Sing Your Song” (2011); music: “Belafonte” (1956), “Calypso” (1956), “An Evening With Belafonte” (1957), “Belafonte at Carnegie Hall” (1959) “Swing Dat Hammer” (1960), “Jump Up Calypso” (1961).

Eartha Kitt

Trained at the Katherine Dunham Company, Harlem’s pioneering Black dance/performance troupe, Kitt quickly became the toast of the European cabaret circuit with her distinctive, purring vocals and friskily witty spin on Tin Pan Alley staples like “Let’s Do It,” “C’est si bon,” and “Love For Sale,” which became hit recordings, as did her now-perennial holiday original, 1953’s “Santa Baby,” a smash despite being banned in the South for its playful, aggressively suggestive and materialistic nature, as delivered by an alluring young Black woman.

Mentored by stage and cinema genius Orson Wells, Kitt quickly enraptured Broadway and later Hollywood – her film output included racially progressive films such as “The Mark of the Hawk” opposite Sidney Poitier, the jazz-themed drama “St. Louis Blues” and as a call girl in the melodrama “Anna Lucasta” (1958). She was a familiar face as herself on television: in her most notable and memorable role, she succeeded Julie Newmar as Catwoman for the third season of the campy pop art phenomenon “Batman,” putting her distinctively purring feline spin on the comic book villainess. Not only did Kitt score a major coup for visibility by appearing on the show – embraced by children and parents alike – in a non-stereotypical role, it was achieved without ever making any reference to her or the character’s race. She became instantly and enduringly iconic.

Kitt’s commitment to performing to desegregated audiences was steadfast: she reportedly kept extra formalwear on hand to outfit wait staff drafted to serve as audience members to add Black faces to her crowds. Her outspoken and unfiltered comments opposing the Vietnam War in front of First Lady Lady Bird Johnson during a White House visit in 1968 led to a blacklisting, and was subject to harassing surveillance and fabricated rumors by the CIA.

She ultimately staged a monumental comeback, and throughout her lengthy career – with later projects like “Boomerang,” “The Emperor’s New Groove” and “Holes” exposing her to successive generations of fans – Kitt championed a number of socially progressive causes. Having cultivated a considerable gay following over the years, she was also an ardent supporter of LGBTQ rights and same-sex marriage, and even when satirizing her own sex kitten image later in life, she put forth an unabashedly pro-sex message for seniors.

Key works, music: “RCA Victor Presents Eartha Kitt” (1953), “That Bad Eartha” (1954), “Down to Eartha (1955); film: “The Mark of the Hawk” (1957), “St. Louis Blues” (1958),“Anna Lucasta” (1958), “Boomerang (1992),” “The Emperor’s New Groove” (2000), “Holes” (2003); television: “Batman” (three guest appearances, 1967-1968).

Sammy Davis, Jr.

Essentially growing up touring and performing on vaudeville and nightclub stages, Davis’ astonishing arsenal of talents – singing, dancing, comedy, mimicry, drumming and more – was honed to razor sharpness: when he, his father and “uncle” – together known as the Will Mastin Trio – were booked as an opening act at the Sunset Strip nightclub Ciro’s in 1951, the response from the Hollywood’s elite was so wildly enthusiastic the headliner insisted they replace her as the main attraction.

From there Davis’s career skyrocketed: he became a top-selling recording artist (the first Black solo artist to have an album hit number one on the Billboard charts), the star of the Broadway hit “Mr. Wonderful” and a fixture on television. His comedic skills as a vocal impressionist were so impressive – and his unabashed admiration for those he imitated (and vice versa) was so endearing – that Davis broke new ground by satirizing white celebrities without significant backlash.

Jerry Lewis and Sammy Davis Jr. photo courtesy of Focus Enterprises

Jerry Lewis and Sammy Davis Jr. photo courtesy of Focus Enterprises

Still, he faced obstacles: his first planned network special, spotlighting the realistic struggles of Black artists, failed to attract sponsors and was scrapped; Las Vegas’ segregation laws kept him from staying at the posh resorts where he packed in standing-room audiences, until his close friend Frank Sinatra, Vegas’ other premiere attraction, forced the city to lift the color barrier; and his interracial romances frequently made him the centerpiece of racist gossip coverage. But even when Davis lost an left eye in a horrific accident in 1954, he could not be kept down, completely retraining himself to dance as brilliantly as before and finding spiritual solace by converting to Judaism.

His bond with Sinatra and Dean Martin as a member of the Rat Pack would further bolster Davis’ image: on screen, they co-starred in a string of popular films, including “Ocean’s 11” and “Robin and the 7 Hoods;” onstage they cavorted together in Las Vegas showrooms in a raucous nightclub act, sending up racial stereotypes with off-color insults, typically with Davis delivering the best, one-upping lines. Soon he starred in his own films, like the dark drama “A Man Called Adam,” and won the Tony Award as Best Actor for another Broadway smash, the showstopper-packed “Golden Boy.”

Even as his career flourished, Davis – a committed civil rights activist – couldn’t always please everyone. Despite his ardent wooing of Black voters during John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign, his impending marriage to white actress May Britt prompted Kennedy’s controlling father to disinvite him to the inaugural. And in 1973, despite becoming the first Black man to spend the night in the White House, his public physical and brief political embrace of President Richard Nixon stoked the ire of Black community.

Still, Davis – ultimately the recipient of an NAACP Springarn Medal, a Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award and the prestigious Kennedy Center Honors – invariably won over his critics the same way he shattered barriers of prejudice, with his sheer, transcendent talent and keen sense of humor, as when, during a guest appearance as himself on the sitcom “All in the Family,” he devilishly planted a kiss on the cheek of the notoriously bigoted Archie Bunker.

Key works, music: “Starring Sammy Davis, Jr.” (1955), “The Wham of Sam” (1961), “Sammy Davis, Jr. Sings and Laurinda Almida Plays (1966), “The Sounds of ‘66” (1966); film: “Anna Lucasta” (1958), “Ocean’s 11” (1960), “Robin and the 7 Hoods” (1964), “A Man Called Adam” (1966), “Sweet Charity” (1969), “Tap” (1989); television: “Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In” (recurring guest star, 1968-1973), “All In the Family” (guest star, 1972).

Dick Gregory

While serving in the Army, the ever-wisecracking Gregory was urged by his commanding officer to enter military talent shows, and as a civilian he became a rising star in the standup scene, with insightful, boundary-pushing and above all funny material commenting on race, politics and society that appealed to Black and white audiences alike. After being spotted by Playboy publisher Hugh Hefner, a planned one-night gig at Chicago’s flagship Playboy Club in 1961 turned into an extended stint that eventually brought him to national prominence with club dates, chart-topping comedy albums and bestselling books.

His ability to genially but pointedly comment on the oft-taboo topics of race and politics distinguished him as part of a new breed of hip, convention-challenging comedians like Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl, while paving the way for subsequent comics like Richard Pryor to go even further.

When Gregory appeared on “The Tonight Show,” he broke convention for Black artists by insisting on joining host Jack Paar for a chat at the desk following his performance. Gregory’s comedy frequently offended white conservatives, who condemned and banned his act: when the University of Tennessee revoked his speaking engagement on campus in 1969, students there successfully sued to reinstate his invitation.

Gregory had activism in his veins, and his commitment to the causes he was passionate about overshadowed his comedy career. He spoke out for the civil rights movement in Selma, Alabama, in 1963, and effectively connected the cause to the prevailing antiwar sentiments of the Vietnam era. Gregory became a proponent of various causes well before they became fashionable or entrenched – including Black voting rights, Native American rights, feminism, veganism and animal rights, nuclear power and the anti-apartheid movement – but occasionally pushed forward less accepted conspiracy theories (including those involving the moon landing and 9/11). He also moved into politics: a stunt-ish run for mayor of Chicago in 1967 led to more a somewhat more serious campaign for the U.S. presidency the following year – an act that landed him on the infamous “enemies list” kept by President Richard Nixon.

Key works, comedy albums: “Living In Black and White” (1961), “Dick Gregory Talks Turkey” (1962);books: nigger: An Autobiography by Dick Gregory (1964), Write Me In! (1968).

Cicely Tyson

An in-demand fashion model, Tyson transitioned to acting and, after a series of Broadway triumphs, she scored a major coup, becoming the first Black actress to appear in the central cast of a television drama, opposite George C. Scott in the short-lived, controversial and critically acclaimed “East Side/West Side” in 1963. On film, she’d score a key role opposite Sammy Davis, Jr., in the jazz/addiction drama “A Man Called Adam” and a wealth of TV guest spots – on series including “I Spy,” “Mission: Impossible,” “Gunsmoke” and even the daytime drama “Guiding Light,” playing one of the earliest regular Black female soap opera characters.

Tyson’s role in the 1972 film “Sounder” would rocket her career into another stratosphere, earning her critical acclaim and Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations for her role as the matriarch of a troubled sharecropper family. A series of riveting, socially relevant television performances focusing on vital Black stories would follow: aging through nine decades as a former slave embracing the 1960s civil rights movement in “The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman;” as Kunta KInte’s mother in the epic miniseries “Roots;” playing the wife of Dr. Martin Luther King in the miniseries “King;” portraying Harriett Tubman in “A Woman Called Moses;” and as the innovative public school teacher in “The Marva Collins Story.”

For decades, Tyson put her unforgettable stamp on the roles she played – a short list includes “Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All,” “A Lesson Before Dying,” “Fried Green Tomatoes,” “Diary of a Mad Black Woman,” “The Help” and “The Trip to Bountiful” (reprising her Tony-winning stage role) – culminating with her recurring appearances on the hit ABC drama “How to Get Away With Murder,” for which she’s been nomination five consecutive times for an Emmy Award for Outstanding Guest Actress in a Drama Series, the most recent coming in July of 2020.

To date, she’s collected three of the 15 Emmys she’s been nominated for, along with an Honorary Oscar (the first Black female recipient), a Tony, a Peabody Award, the NAACP Spingarn Medal and dozens of other accolades, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom Award, the nation’s highest civilian honor, awarded to her by President Barack Obama. Tyson’s trophies stand as a testament to her skills as an artist, her continued commitment to telling resonant stories about the experiences of people of color in America, and her long, distinguished record of actively advancing civil rights causes.

Key works, film: “Sounder” (1972), “Fried Green Tomatoes” (1991), “Diary of a Mad Black Woman” (2005), “The Help” (2011); television: “The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman” (1974), “Roots” (1977), “King” (1978), “A Woman Called Moses” (1978), “The Marva Collins Story” (1981), “Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All” (1994), “A Lesson Before Dying” (1999), “The Trip to Bountiful” (2014), “How to Get Away With Murder” (2015-2020).

Nichelle Nichols

As a teen the multitalented Nichols was recruited by bandleader Duke Ellington to sing with his orchestra on tour, followed by a stint touring with Lionel Hampton and various musical theater efforts. She was spotted in a Chicago stage production by Playboy publisher Hugh Hefner, who promptly booked her as a cabaret performer in his flagship Playboy Club in 1962.

Photo courtesy of Desilu Productions

Photo courtesy of Desilu Productions

She was just getting a start in television when producer Gene Roddenberry cast her in a racially themed episode of his military series “The Lieutenant” in 1964; two years later they would reteam for Roddenberry’s visionary sci-fi series “Star Trek.” The role of Lt. Uhura was an exceedingly competent, capable member of the starship Enterprise’s command crew– a then-rare instance of a Black person in a role of respect and equality, rather than in a servile position. For countless young people of color watching at home, Uhura’s place on the Bridge symbolized Black people having an important place in the future.

Eager to return to musical theater, Nichols had planned to exit the series after the first season, but was dissuaded by Dr. Martin Luther King, a fan of the show, who explained Uhura’s resonance within the Black community to her. Later, in 1968, she and co-star William Shatner would shatter convention by sharing television’s first interracial kiss – despite nervous network expectations, the viewer reaction was overwhelmingly positive.

Though the series would run only three-seasons, it eventually evolved first into a cult classic in syndication, then as a hugely successful film series, and ultimately as an enduring phenomenon and constantly renewing multimedia franchise. Nichols would routinely reprise her role over the course of 25 years, becoming one of the first sci-fi icons of Black and female empowerment.

Because of “Star Trek’s” popularity among smart, aspirational fans – including future President Barack Obama – Nichols was asked by NASA to help recruit women and minorities into its space program. Her efforts were wildly successful for many years: her recruits included Sally Ride and Guion Bluford, respectively America’s first female and Black astronauts. With countless other men and women of all colors pursuing careers in STEM-related fields because of their love of the series and affinity for Uhura, Nichols’ legacy is certainly one that’s profoundly impacted the future.

Key works, television: “Star Trek” (1966-1969); film: the “Star Trek” film franchise (1979-1991); music: “Down to Earth” (1967).

Diahann Carroll

With her flawless features, Carroll seemed destined for a modeling career, becoming a familiar face in national magazines like Ebony. But she quickly made an even bigger impression on television when as a singer she won the TV talent competition “Chance of a Lifetime” in 1954, launching a vibrant nightclub career. Supporting roles in Hollywood films followed, including “Porgy and Bess” and “Paris Blues,” and on the Broadway stage, in “House of Flowers” and “No Strings” – she won a Tony for the latter production in 1962 (the first Black winner, male or female, in a leading role), a Grammy for the cast album and received her first Emmy nomination the following year for a guest role on “The Naked City.”

Photo courtesy of Aaron Spelling Productions

Photo courtesy of Aaron Spelling Productions

Her career triumphs brought her back to television for a busy stint as a guest actor and performer on scripted series, talk shows and variety series, until 1968 when she was cast as the lead in “Julia.” The first-ever weekly sitcom to star a Black woman in a non-stereotypical role as a servant, Julia Baker was instead a nurse and widowed single mother dealing with topical issues. The role earned Carroll a Golden Globe Award and an Emmy nomination, both firsts in her categories for a Black woman. She later moved on to further career heights, earning an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress for 1974’s “Claudine,” plus further awards attention for numerous television movies and series roles and guest spots.

In the 1980s Carroll changed TV again: at her own suggestion, noting a lack of Black visibility in the then-hot nighttime soap opera genre, she famously integrated the cast of the “Dynasty,” playing Dominque Deveraux, a ruthless, scheming adversary for Joan Collins’ villainous Alexis whom viewers immediately embraced – equal in status, wealth and sheer bitchiness, as Carroll had requested. On stage, she assumed roles in hit productions that had previously only been played by white actresses, such as “Agnes of God” and “Sunset Boulevard,” an apt capstone on a career highlighted by redefining the color of the characters audiences had grown accustomed to seeing at center stage.

Key works, television: “Julia” (1968-1971), “Dynasty” (1984-1987), “A Different World” (guest actress, 1989-1993), “Grey’s Anatomy” (guest actress, 2006-2007), “White Collar” (2009-2014); film: “Paris Blues” (1961), “Claudine” (1974), “Eve’s Bayou” (1997); music: “Best Beat Forward” (1958), “The Magic of Diahann Carroll” (1960).